A raw material heaven missing the export train

August 09, 2025

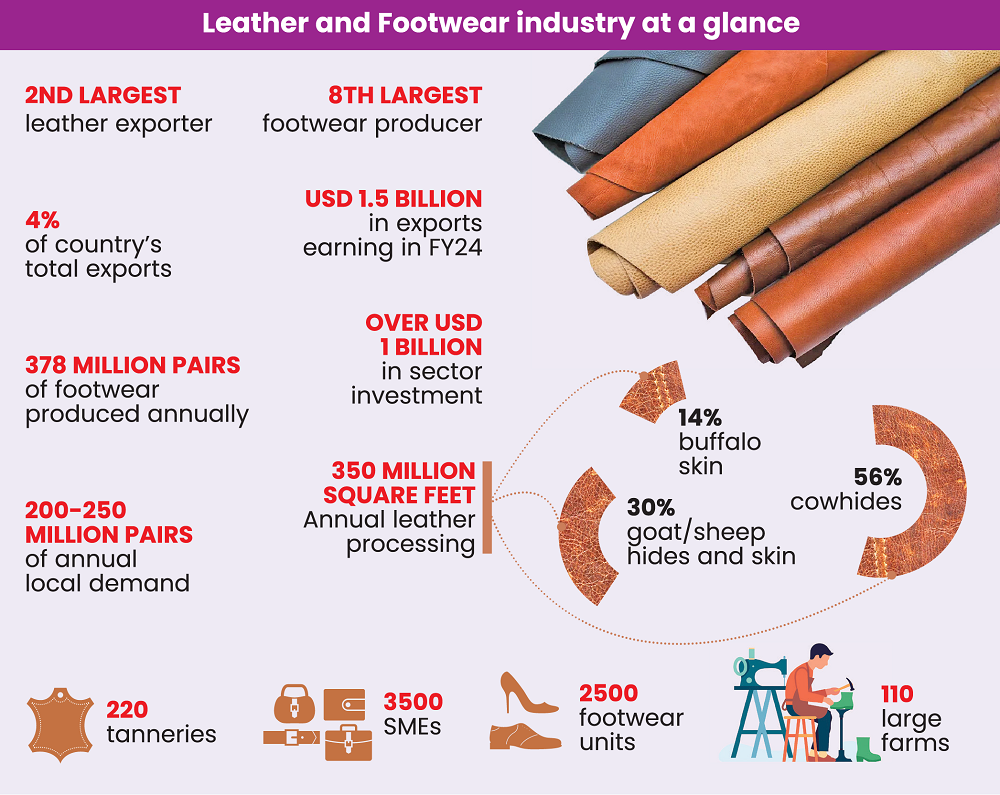

Beneath the celebrated export engine of the apparel sector lies a quieter paradox: the leather sector, blessed with raw material abundance and an eager workforce, has failed to replicate the same global momentum.

While the apparel industry thrives despite lower value addition, Bangladesh’s leather sector, rich in potential, remains underleveraged.

Industry experts say that although value addition in leather can reach as high as 90%, the current rate struggles to exceed 65%.

The mismatch between resource endowment and export performance raises serious questions: why hasn’t Bangladesh’s leather sector taken off? And what structural, policy, or strategic gaps are holding it back?

Industry professionals and policy analysts noted that Bangladesh’s supply of rawhide remains relatively secure, thanks to the annual surge in animal sacrifice during Eid festivals, which ensures a steady stream of raw materials.

However, this natural advantage has not translated into high value addition. Manufacturers struggle to move up the value chain, primarily due to the absence of domestic demand for premium leather goods and accessories.

For export-oriented products, the situation is even more constrained. Value addition often drops to as low as 30%.

What’s stopping us?

A key bottleneck is the lack of certification from the Leather Working Group (LWG), a globally recognised body that promotes sustainable practices and transparency across the leather supply chain.

“We have the raw materials and the workforce, but without LWG accreditation, our tanneries are locked out of premium global markets,” said Professor Md Mizanur Rahman, former director of the Institute of Leather Engineering and Technology at the University of Dhaka.

“It’s not about wages or fire safety anymore; the global leather trade now hinges on environmental compliance. And that’s where we are failing.”

“The Central Effluent Treatment Plant (CETP) in Hemayetpur was meant to fix that, but it’s been dysfunctional from day one. That failure alone has shut the door on international buyers,” he said.

According to him, when the tanneries moved out of Hazaribagh two decades ago, the relocation was supposed to come with modern compliance infrastructure.

“That never fully materialized,” said Mr. Rahman.

“Garments adapted to global standards through Accord and Alliance. Leather needs the same commitment. But without LWG certification, we are stuck in a low-value loop.”

There is scope to ensure 85% to 90% value addition through quality tanning and manufacturing of high-end products, he said.

“Bangladesh has over 200 tanneries and 220 leather and leather product manufacturers, but we have very limited tanneries outside the Hemayetpur cluster that are LWG-certified,” said Mr. Rahman.

Some of them are SAF Tanneries (Akij Group), Superex in Khulna, and RIFF Leather Limited – an enterprise of the T. K. Group, which are fully compliant, end-to-end producers from raw hides to finished leather.

Mr. Rahman also said that inside the Hemayetpur cluster, at least 8 to 10 tanneries have the capacity to achieve LWG certification.

“But they can’t–simply because the central effluent treatment plant (CETP) is non-functional,” he noted.

In this situation, no tannery within Hemayetpur has achieved LWG certification. That’s a huge bottleneck holding back export growth, he remarked.

Potentials not met

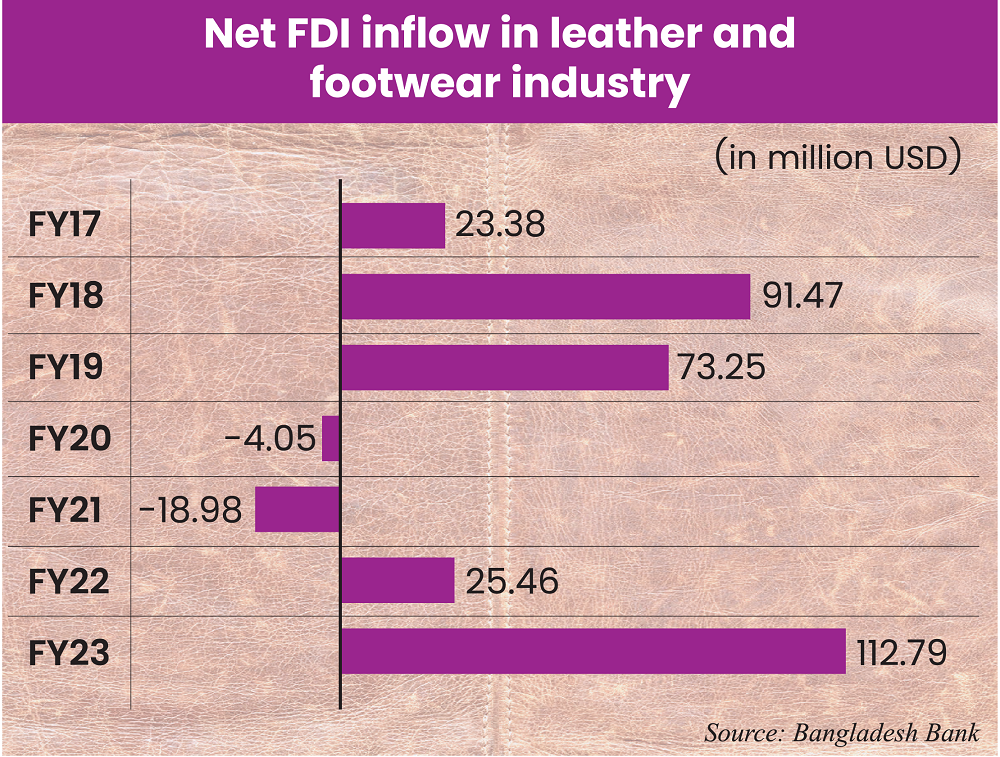

Bangladesh is not doing well in the international market. Shipments of leather and leather products in FY 24 fell by 11.6 % year-on-year to $1.03 billion in fiscal year 2023-24. It was $1.17 billion in FY 23, according to data from the Export Promotion Bureau (EPB).

In the current fiscal year, Bangladesh exported $933 million during the July-June period, compared to $847 million in the first 10 months of the fiscal year, according to EPB data.

Professor Mizanur Rahman believes that the local leather sector has the potential to increase exports to $10 billion to $12 billion by using locally available leather to cater to the global market.

“Globally, Bangladesh holds just 0.7% of the leather market, despite having abundant raw materials thanks to our large livestock base.”

“If the Hemayetpur CETP was fixed and tanneries became compliant, we could easily double or triple export volumes—from $1.2 billion to $4–5 billion annually,” said Professor Rahman.

“These tanneries are running at only 10–20% of their capacity because they can’t access high-value export markets. With LWG compliance, they’d be fully booked.”

“With compliance, exporters can charge 15% more for the same leather. That’s a massive revenue boost,” he said.

According to the Bangladesh Tannery Association, the tannery industry is capable of producing 300 million square feet of leather each year.

“We’re operating under severe constraints,” said Md Shakawat Ullah, secretary of the Bangladesh Tanners Association.

“Out of 162 tanneries in Hemayetpur, 142 are currently operational. We have the capacity to process around 300 million square feet of leather annually, but a lack of compliance, especially due to the incomplete CETP, is holding the industry back.”

He added that the Chinese company responsible for constructing the central effluent treatment plant (CETP) left the project incomplete in 2021, making it impossible for tanneries to meet international environmental standards.

“Without full CETP commissioning, we cannot achieve LWG certification, which limits our export potential.”

Shakawat also highlighted the financial strain many producers face due to low prices in the domestic market and payment delays from foreign buyers, particularly from China, our biggest customer.

“We haven’t received adequate support from banks either, which has worsened our cash flow crisis,” he noted.

Shahjada Ahmed Roni, managing director of Jihan Footwear Limited in Cumilla, told Industry Insider that pricing has been a challenge for their business to sustain.

“We run a fully compliant factory, but that comes at a cost. Salaries alone have increased by 30%, yet buyers are not adjusting prices accordingly. Operating under strict compliance standards without fair pricing support is unsustainable.”

He said the recent tariff issue with the U.S. market brought new uncertainties.

“As a result, buyers are hesitating—they’re either delaying orders or not placing them at all. We used to get 90 to 120 days for order processing, but now there’s a six-month gap in our export cycle.”

“Countries like Vietnam and Cambodia have already taken the lead. Their labor costs are lower, and they’re better positioned with international policies. We can’t even progress locally due to internal constraints,” he said.

“Domestic raw material prices have doubled, but international buyers haven’t increased their rates. This mismatch is forcing us to sustain significant losses, sometimes up to 50%.”

“With bank interest rates as high as 14%, and hidden costs pushing it to 18%, it’s extremely difficult to stay competitive.”

“We source all our leather locally, but only a handful of tanneries in Bangladesh, around six, are LWG-certified. Most buyers nominate their own suppliers, and we’re often left out of the loop. If we had more compliant tanneries, we could have more bargaining power and better price points,” he said.

The biggest issue is that our ecosystem is incomplete. With only a few compliant tanneries, we lack depth in our supply chain. That leaves us at the mercy of high-priced suppliers and limits our ability to scale or compete globally, he said.

Even the orders that were confirmed are being postponed. For instance, if a buyer committed to 10,000 pairs, they’re now taking only 3,000. That’s less than a third of the order.

“Everyone is waiting for price drops, but we can’t hold out forever,” he said.

“Bangladesh’s ambition to revive its leather exports critically depends on achieving LWG certification, a goal that remains elusive as long as the central effluent treatment plant (CETP) in Savar remains non-compliant,” said Syed Nasim Manzur, on May 25 at a discussion in Dhaka, organized by the Dhaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DCCI).

The failure to operationalise the CETP and meet LWG environmental compliance standards will continue to exclude Bangladesh from the premium global market, Manzur said, also the president of the Leathergoods and Footwear Manufacturers & Exporters Association of Bangladesh (LFMEAB).

“Without LWG certification, we are invisible to major global buyers who demand verifiable sustainable sourcing,” he said.

Although 220 tanneries relocated to Savar from Hazaribagh in 2017, the promised environmental infrastructure, particularly the CETP, remains incomplete.

This has prevented Bangladesh from qualifying for LWG audits, resulting in a steep fall in leather exports.

Manzur said resolving the CETP issue is the single most important factor for export recovery and growth, and proposed the appointment of an internationally certified CETP operator, backed by green financing, to bring the plant up to LWG standards.

“Once we have a functioning, audited CETP, leather exports can double,” he said.

He highlighted global trends and said major brands actively seek sustainable leather sources.

“There is a window of opportunity for Bangladesh, but it won’t remain open indefinitely,” he said.

Mr. Manzur urged policymakers to offer the same support to leather as is provided to the readymade garment sector, including bonded warehouse facilities, duty-free import of CETP-related machinery, and reimbursement of audit costs.

“Bangladesh’s leather sector can thrive post-LDC graduation,” he said, “but only if we deliver on compliance, especially through a fully operational, LWG-ready CETP.”

Chief collection and merchandising manager at Bata Bangladesh, Mizanur Rahman, told Industry Insider that environmental compliance is a non-negotiable requirement for global sourcing.

He also emphasized the importance of a robust marketing strategy, stating, “Bangladeshi products are often OEM-driven, without strong brand identity or value recognition.”

Vietnam’s success

While Bangladesh is still struggling to take off, Vietnam, a country that started later compared to Bangladesh, has already soared into the skies. Today, its leather and footwear exports are worth more than $20 billion annually.

Bangladesh, meanwhile, scrapes by under $1.2 billion, often exporting semi-finished crust leather instead of finished goods.

Vietnam’s success story wasn’t born overnight. After joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2007, it aggressively pursued trade deals, established export processing zones (EPZs) specifically for leather and footwear, and invited global giants such as Nike, Adidas, and Puma to co-invest.

Vietnam didn’t just export leather; it exported finished shoes, bags, and branded accessories.

Crucially, the government offered tax breaks, one-stop regulatory clearance, and worker training programs tailored for footwear manufacturing. LWG certification became the standard rather than an exception, and partnerships with international brands helped scale the business rapidly.

Vietnam’s footwear industry is primarily based on synthetics, rather than just leather. But even then, they’ve made remarkable progress. After China, Vietnam is the second-largest exporter of footwear globally, with exports reaching nearly $30 billion, according to Professor Mizanur Rahman.

“In comparison, we’re stuck at just around $1 billion. Yet we have the raw materials, as I said—we could easily reach $10 to $12 billion in exports if we fixed some key issues.”

Mr. Rahman said many factories are just sitting idle. Many plot holders aren’t running tanneries at all; they’re holding on to the land as an investment. What was once bought for Tk 1 million can now be sold for Tk 100 million; it’s become a business in itself.

Some have leased the plots to others, while many run operations just during the Qurbani season, renting tanneries for a few months. These short-term operators don’t care about pollution or water usage. That’s not on their radar, Rahman said.

“Then there’s the syndicate problem.”

Currently, only 10% of our tanneries are operating at full capacity. When demand increases and 80 to 100 tanneries go into full operation, raw materials will suddenly become scarce.

“The same people who now buy hides at Tk 500 will start hoarding and selling at exorbitant prices like Tk 5,000. That’s how broken the supply chain is; it’s entirely demand-driven.”

However, the chief collection and merchandising manager at Bata Bangladesh, Mr. Mizanur Rahman, sees hope in Bangladesh’s ready workforce.

“Behind every process, whether production, quality control, or compliance, are people. The industry’s long-term success depends on developing a skilled, future-ready workforce.”

“Bangladesh needs more targeted initiatives focused on training, upskilling, and retaining talent across all levels of the leather value chain,” he remarked.

Bangladesh stuck in a loop

Despite having an abundant supply of rawhide, Bangladeshi exporters spend around Tk 10 billion annually to import LWG-certified finished leather.

Industry experts attribute this paradox to the shortcomings of domestic tanneries, which continue to struggle to meet international compliance standards. The core issue, they argue, is the non-functional state of the central ETP at the Savar Tannery Industrial Estate.

According to a study by the Bangladesh Investment Development Authority (BIDA), leather and footwear manufacturers mostly refrain from sourcing raw materials from local companies due to the absence of a CETP at the Savar Tannery Industrial Estate.

As a result, Bangladesh is unable to fully harness its export potential while simultaneously expending a significant amount of foreign currency to procure raw materials from overseas sources, it added.

According to the BIDA report, there are 139 LWG-certified companies in India, 103 in China, 68 in Italy, 60 in Brazil, 24 in Taiwan, 17 in Spain, and 16 each in South Korea and Turkey, and 14 in Vietnam.

“We are still struggling with CETP and solid waste management at the Savar estate. Without meeting ESG standards, we can’t move beyond the $1 billion export mark,” said Professor Abu Eusuf, executive director of Research and Policy Integration for Development (RAPID), a local think tank in Bangladesh.

“Vietnam and Bangladesh were once at a similar stage. Now Vietnam exports over $20 billion in leather and footwear, while we remain stuck due to non-compliance,” he said.

“The Leather Development Authority should be placed outside BSCIC and the Ministry of Industries, under an independent structure to ensure focused and effective governance.”

“We have all the raw materials locally available except for some chemicals. If we manage compliance, this sector alone could earn $8 to $10 billion annually,” added Professor Eusuf.

“Everyone in the government agrees in principle, but without fixing CETP and ensuring proper common facilities, even LWG-certifiable factories can’t move forward.”

“The National Task Force mostly sets rawhide prices during Qurbani, but it hasn’t provided the big policy push the leather sector urgently needs,” he said.

Echoing the same, Professor Mizanur Rahman said there are too many associations in the leather sector—three, four, even five.

“They spend more time blaming each other than solving the real problems. The Ministry of Environment sets the same compliance standards for tanneries as it does for food-processing factories like Pran or ACI.”

“That’s absurd. Leather is one of the most chemically intensive and polluting industries in the world,” said Mr. Rahman.

“You can’t regulate tannery effluent using food industry benchmarks—these are different universes in terms of waste and treatment requirements,” he said.

On the other hand, Mr. Rahman from Bata Bangladesh believes the country needs long-term vision and cohesive policy reformations.

“The absence of consistent incentives tied to global compliance and sustainability standards continues to limit the industry’s ability to scale and attract international buyers,” he said.

However, he believes that Bangladesh’s large and growing population provides a significant domestic consumption base that can serve as a strong foundation for brand development.

“There is a need for clear and consistent policy support to encourage the growth of local brands, promote entrepreneurship, and create a vibrant ecosystem that balances both export and domestic priorities,” he concluded.

Md Asaduz Zaman is a journalist, specializing in Bangladesh’s economy, environment, and agriculture sectors.

Most Read

Electronic Health Records: Journey towards health 2.0

Making an investment-friendly Bangladesh

Bangladesh facing a strategic test

Understanding the model for success for economic zones

Bangladesh’s case for metallurgical expansion

How a quiet sector moves nations

A raw material heaven missing the export train

Automation can transform Bangladesh’s health sector

A call for a new age of AI and computing

You May Also Like